Declining sales and accumulated debt forced the sale of the combine division and closure of the plant

In this final instalment of our four-part series on the Massey Ferguson combine plant in Brantford, Ont., the story wraps up with a look at the plant’s final days and what was left unfinished as the company abandoned combine manufacturing in the 1980s.

As the 1980s began, the evolution toward fewer, larger farms had taken hold. That meant farmers were now buying fewer, larger machines. It was an evolution of the equipment market that many executives in the industry, and especially at MF, failed to recognize early on.

Other stories in this series:

- A look back at a Massey Ferguson milestone

- Brantford plant supported harvest brigade

- Engineers keep a close eye on the competition

Added to that was a worldwide recession and record high interest rates, along with low commodity prices for farmers. The impact of that was inevitable.

Overall, combine sales reported by all brands in the United States in 1979 amounted to 32,246, but by the end of 1985, those numbers fell an astonishing 74 percent to just 8,402. By then, sales numbers for the domestic market in Canada weren’t much better, nor were they anywhere else in the world.

By 1984, MF losses since 1977 had exceeded $1.4 billion, and the company had bank debts in 1980 of $1.6 billion.

In a 1984 speech, Victor Rice, MF’s then chair and chief executive officer, said: “We went back to square one and asked ourselves: are we manufacturers, are we marketers, are we deal-makers? In the end, we decided we are marketers first.”

It was clear MF no longer believed it needed to build the machines it sold.

MF was bleeding red ink and needed things to change quickly. The creation of Massey Combines Corp. in 1985 was a big part of the effort to stop the hemorrhaging.

In 1985, Massey-Ferguson reorganized itself into a number of divisions and sold off its combine business, including the Brantford plant. To do that, MF created an independent company called Massey Combines Corp (MCC) and gave it all the MF combine operations. In doing so, MF eliminated its largest money-loosing venture and shed a large portion of its debt.

The quotation, “A renewed company has emerged, poised for greater profitability, determined to create value for shareholders,” was emblazoned across the cover of Massey-Ferguson’s 1985 annual report. But whether the extensive reorganization that MF undertook would lead to greater value for shareholders still remained to be seen. One thing seemed certain, though, MCC, which was created to accommodate the renewed company structure, was going to have a tough go of it.

Dick Brown, MCC’s vice-president, put forward an optimistic face. He said during a media interview in 1986 that he expected combine sales in the U.S. to rebound to around 21,000 units.

It didn’t.

From the start, MCC’s debt load was staggering. MF had pared off assets worth about $296 million to create the new company, but along with that it transferred more than $206 million in long-term debt.

MF retained a $32.2 million stake in the new company, allowing MF to profit in the unlikely event MCC actually did make money.

But despite the economic difficulties that Brantford combine production faced in the 1980s, some exciting research projects were underway. Before the creation of MCC, MF’s rotary combine project, the TX900, which was initially proposed in 1976, was still progressing at the start of the decade, and MF had decided to get back to work on its conventional models, too.

Starting in 1980, the TX800 project began, which was devoted to developing an entirely new conventional combine. The plan was to create a line-up comprising four models designated TX801 to 804. These machines would have cylinder widths of 40, 50, 60 and 70 inches, respectively. And they would incorporate several new design elements over the previous 800-series machines.

The TX800 prototypes were hand built in the Harvesting Engineering Centre in Toronto and sent to Nebraska for field trials. They still bore some resemblance to the earlier 800-series models, but the cab had a new shape to it, as did the engine compartment.

There were also major changes under the sheet metal. The new look around the engine compartment incorporated a redesigned air intake arrangement. The new combines would use 1000 Series Perkins diesel engines and a higher-performance drive train.

The drive train upgrades included a hydrostatic transmission with a high-capacity pump that was connected to a belt-driven, torque-sensing traction drive system.

At the same time, the rotary TX900 project was continuing, and it had been under development for much longer than the TX800.

Initially, the plan was to include three models in the TX900-series: the 901, 902 and 903. The 903, with its 27-inch rotor, was seen as the potential replacement for the 750 and was the main focus of initial engineering efforts.

One of the most innovative features on the 900 machines was to be the incorporation of a load-sensing hydraulic system for the threshing rotor. It was intended to use hydraulics to maintain the correct concave setting to accommodate varying load rates and prevent plugging.

The 903 and 904 designs, though, hadn’t proven to be everything that was hoped for. They were prone to an unacceptable fore-aft pitching problem, and significant design changes had to be made. And engineering department estimates forecast that continuing development costs in 1981 would reach $3.453 million. Testing on the 904 was originally expected to last until 1984 with the 903 completing in 1985.

Eventually, financial considerations would result in the dropping of both the TX900 and TX800 projects in 1985. But this time it wasn’t just MF’s financial problems that were the cause. It was White Farm Equipment’s bankruptcy, another victim of the farm-economy crisis.

Coincidently, White Farm Equipment was also building its rotary combine in Brantford. To disperse the company’s assets, the receiver handling White’s bankruptcy offered to sell the White rotary combine to MF before it splintered off the Brantford plant to MCC.

Management at MF decided it would be more cost efficient to buy the White design and put that into immediate production rather than continue developing its own.

Faced with all that, the TX900 project was dropped, and at the same time, so was the new conventional TX800. MF was putting all of its combine eggs in one basket, the White rotary.

For a while, MF even marketed White 9720 rotary machines with both WFE and MF decals on the side. Boasting that it now owned the White combine was a key part of the company’s initial advertising. And the 9720 was a giant for its time, powered by a 10.5-litre Perkins V-8 with a 31.5 inch diameter rotor.

Eventually the dual badging of WFE and MF together on the 9720 would end, and MF developed modified versions of the smaller White models, which it numbered 8560 and 8570.

Production of the White rotaries continued at Brantford under MCC ownership, but by 1988 MCC had accumulated debt worth $90 million more than its estimated asset value. It was bankrupt.

After MCC failed, the White-based combine technology was again put on the open market. It was bought by Vicon, a Scandinavian company that had a small manufacturing plant in Portage la Prairie, Man. Vicon had been manufacturing implements there, which were marketed by Canadian Cooperative Implements Ltd. It then sold the combine line to auto parts manufacturer Lindamar, which had been supplying production parts.

MF stepped up and bought back the conventional combine business for the bargain price of $8 million from the bankruptcy receiver. That included plant tooling and inventory, but not the Brantford plant. This allowed MF to take back the lucrative parts business for the existing conventional combines already in service.

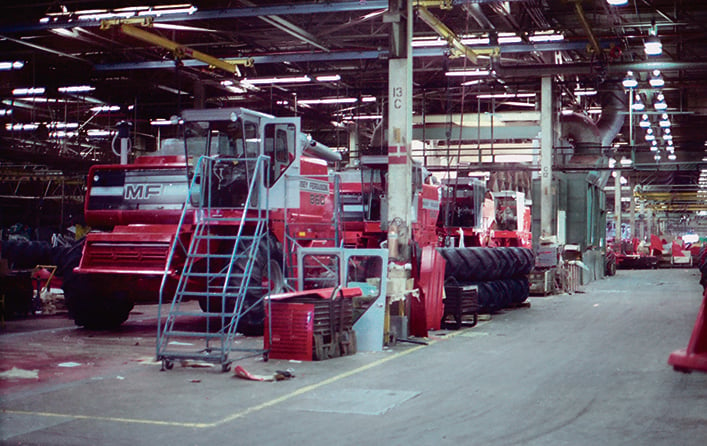

As for the Brantford plant, after nearly 175,000 conventional combines had gone down the assembly line, along with a much smaller number of rotaries, it closed, and would never again see combine production.

Brantford was a plant built to include room for expanding production and upgrades in technology and was meant to last well into the future.

A.A. Thornbrough, MF’s president who proudly posed for photos with dozens of dignitaries on opening day in 1964, probably could not have imagined his flagship factory would have a life of barely 24 years.