PRAIRIE people take pride in our reputation as one of the world’s great wheat growing regions. And rightly so.

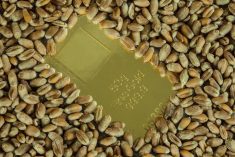

The wheat stalk with a full head of plump kernels is one of our defining symbols. High quality hard red spring wheat and durum are signature products. They enhance breads, pastries and pastas around the world.

Producing any kind of grain in the Canadian Prairies has its challenges. A short growing season, uncertain rainfall, strong winds, insects and disease can conspire to cut yields or trash the quality of a crop in any given year. Every farm family has suffered such disappointments.

Read Also

Growth plates are instrumental in shaping a horse’s life

Young horse training plans and workloads must match their skeletal development. Failing to plan around growth plates can create lifelong physical problems.

Given these odds, it’s no wonder that prairie farmers take great pride in the fine reputation of our wheat and durum. It takes hard work, good research, skill and determination – and decent weather – to get a good crop.

It also takes discipline and organization to ensure that high quality and uniformity are achieved across a vast growing area. Our customers value that quality protection and reliability. This high quality reputation relies on the quality control system of the Canadian Grain Commission, combined with the marketing expertise of the Canadian Wheat Board.

But it is really generations of prairie grain farmers who have been the driving force toward higher quality, higher value wheat. Working within our climate and soil restraints, farmers have wisely understood that these can be turned into competitive advantages, but only if we focus on the right strategy. Our yields will never be as high as those in better rainfall areas, but our quality can be, and is, the best.

Last month, federal agriculture minister Gerry Ritz announced that one of the key tools of the quality control system, kernel visual distinguishability, will be tossed out at the end of July. Favouring higher yields over quality, Ritz is pushing farmers to convert to growing “new crop varieties tailored to livestock nutrition and biofuel production.”

Getting rid of KVD in a hurry may ease the registration of new varieties. Growing more acres of higher yield, lower quality, lower priced grains may well aid the biofuel and livestock industries.

But these changes come with added costs. Equipment to test for quality and variety is not yet available . Who will bear the liability for mixed or contaminated shipments that customers reject?

More stringent and vigilant systems for grain handling and transportation will have to be implemented. Who will pay for that?

However, the real cost is not just financial. It includes values, pride and identity. What is a good reputation worth? What can compensate for the pride and satisfaction that western grain farmers take in knowing that they reliably supply the highest quality of milling wheat for the bread baskets of the world?

The KVD decision is hasty and unwise. The minister should remember the old adage: Act in haste and you will regret in leisure.

Nettie Wiebe is a farmer in the Delisle, Sask., region and a professor of Church and Society at St. Andrews College in Saskatoon. She is also the federal NDP candidate for Saskatoon-Rosetown-Biggar.