Boehm is vice-president of the National Farmers Union.

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture recently endorsed a recommendation that the mandate and governance of the Canadian Grain Commission be changed.

Unfortunately, the change endorsed by the committee will imperil grain producers and ultimately allow grain companies to fundamentally restructure agriculture in their interests and for their own gain.

Section 13 of the Canada Grain Act, which defines the CGC mandate, reads as follows:

“Objects of the Commission

13. Subject to this Act and any directions to the Commission issued from time to time under this Act by the Governor in Council or the Minister, the Commission shall, in the interests of the grain producers, establish and maintain standards of quality for Canadian grain and regulate grain handling in Canada, to ensure a dependable commodity for domestic and export markets.”

Read Also

Crop profitability looks grim in new outlook

With grain prices depressed, returns per acre are looking dismal on all the major crops with some significantly worse than others.

The phrase, “in the interests of the grain producers” is not a superfluous line in the Act. It is fundamental to the direction of the CGC in fulfilling its function.

The recognition that the CGC must act “in the interests of the grain producers” is the result of, and recognition of, abuses farmers suffered at the hands of grain companies and railways a century ago.

Cheated by the grain companies on weight, quality, price and even delivery opportunities, farmers were faced with a stark choice of “take it or leave it.” The implementation of the Canada Grain Act in 1912 put an end to these blatant abuses by putting the interests of farmers first and foremost.

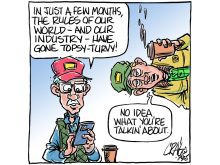

Unfortunately, this type of behaviour by grain companies is just as likely to occur today if that protection is removed, especially given the increased corporate concentration in the grain business.

Today, Canadian grain companies are merging and reducing competition on the Prairies, while a handful of corporations dominate the global grain trade. Without a strong regulator with a mandate to act “in the interests of the grain producers,” the consequences for Canadian farmers will be grave indeed.

Make no mistake; these grain companies recognize the economic gains they will make at the expense of farmers if the mandate changes over time. This will be an incremental, but relentless, process.

The Commons ag committee has endorsed the removal of the line, “in the interests of the grain producers” and agreed to substituting it with “in the interests of all Canadians.”

While this may appear on the surface to be a relatively benign change, the reality is that treating grain companies and farmers as equals is pure folly. It does not recognize the severe power imbalances that exist between powerful corporations and individual farmers. In reality, the new mandate will not mean “in the interests of all Canadians” but instead will mean “in the interests of the grain companies.”

This will be a relatively seamless process accomplished by appointing a CGC chief commissioner who is friendly to grain company interests. Such an appointment, coupled with the removal of CGC assistant commissioners, who have served as trusted intermediaries for farmers in their dealings with the commission, grain companies and the railways, would harm farmers.

The CGC, under the changed mandate, could focus on the strict requirements of ensuring quality standards and guaranteeing availability of a dependable commodity for domestic and export purposes, without specifically focusing on the interests of producers. However, this is simply not enough. This rejects the original rationale for forming an agency to look after the rights of farmers.

In regard to quality standards, this itself is subjective, and could very easily result in “specifications” that are so difficult to achieve that farmers would be severely discounted for their grain for no reason other than it is advantageous for those who have the most power to lobby the commission.

Farmers who would like to sell their crop might encounter a situation where they can only achieve the required “quality” by planting grain with certain specifications. If grain companies set those specifications, they will have a vested interest in promoting grain varieties they have exclusive rights over.

The next logical step is that farm-saved seed would be excluded from the system. Handling costs and conditional fees would escalate even more rapidly than they already are.

The changes in the CGC mandate move the CGC from the embodiment of farmers’ rights to a place that specifies farmers’ duties to produce to specifications as ultimately defined by grain companies.

The Commons agriculture committee has accepted the idea of removing the internal advocacy role of assistant commissioners from the grain commission proper, replacing them with an arms-length entity to be called the Office of Grain Farmer Advocacy.

This new body would likely serve as little more than an ombudsman. And since it would be a separate institution from the CGC, it would have almost no effect on how the commission itself operates, let alone have any influence on how grain companies, railways and other players behave toward farmers.

Grain companies and railways will always advance the idea that simple competition is all that is needed to prevent abuse in the system, yet they will always move toward consolidation to remove competition and maximize profits.

This has always meant that farmers come out on the short end of the stick. The current dismal farm income situation confirms this assertion.

The need for a strong CGC that is mandated to serve “in the interests of the grain producers” is as necessary now as it has ever been, perhaps even more so. Anything less will just become another policy folly that drives farmers from the land and leaves those that remain impoverished.