Sometime during the past week, as the Ottawa political system careened toward cobbling together a farm aid package, the broad farm income crisis seemed to become more focused as a “hog sector crisis.”

Newspapers and television newscasts reported on possible “aid to hog farmers”. Politicians began to talk more about the collapse of hog prices and less about the growing disaster in grain and corn values.

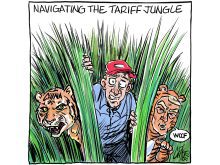

How the transformation happened says much about the role of image, media and lobbying in defining political issues.

Start with the dramatic stories of farmers gassing weanlings, the gruesome discovery of pigs starved to death in an Ontario barn and the sad tales of farmers deciding to dispose of animals because they could not afford to feed them.

Read Also

Invigor Gold variety viewed as threat to condiment mustard

Invigor Gold, the canola-quality mustard developed by BASF, is on a collision course with Canada’s condiment mustard industry. It’s difficult to see how the two can co-exist.

It provided a visual image that captured the attention.

Then came the visibility of the hog lobby itself. On Thursday, industry representatives from across Canada were on Parliament Hill to lay out their tales of dramatic losses, suicidal farmers and broken dreams.

The news conference was well-attended. With an election on in Quebec and rural prosperity an issue, French-speaking reporters began to take an interest in the story of whether Ottawa would offer help before the Nov. 30 vote.

Hog farmers, by protesting and blocking a road last autumn, had won aid from the Quebec government of Lucien Bouchard. Would they be able to do the same in Ottawa?

Quickly, it began to be a “national” story, which certainly helped agriculture minister Lyle Vanclief as he went to a cabinet committee to outline the problem and to try to build a case for farm aid.

Becoming a “national” story helped.

The grain income issue is largely a Prairie concern, affecting a region with little representation in cabinet. Every province has a hog industry and the Canadian Pork Council was happy to provide statistics from different provinces.

And at agriculture committee hearings, the evidence of the damage caused by collapsing hog prices was dramatic.

Manitoba producer Marcel Hacault told MPs he had been able to save $8,000 over four years in his Net Income Stabilization Account. He withdrew it. It covered a month and a half of losses.

Prince Edward Island farmer Randall Affleck said a neighbor had sold his last 14 hogs at a loss of $55 each. On P.E.I., a farmer with a $10-per-hour job would have to work most of a day to cover the loss on each hog. “That’s ridiculous.”

It was dramatic evidence in need of strong television visuals.

By week’s end, television reporters were calling around, asking for the names of Ottawa-area hog farmers willing to allow them to film for backdrop to these Parliament Hill stories.

The farm income crisis had become a “hog sector crisis,” although by revenue it is less than half the size of the affected grain sectors. Vanclief and the politicians knew the problem was broader but they answered the questions posed to them. Those pushing for a broad farm aid package were happy to ride the visually dramatic hog crisis toward their goal.