I HAVE just moved back to Toronto after almost 20 years in Saskatoon. When friends from western and rural Canada come to visit they are sometimes overwhelmed by the noise, the speed and the wealth of this city.

What they sometimes miss is how much poverty has grown here and how that wasn’t always the case.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s I lived downtown. It was crowded and busy then too, but one of the things I liked most about Toronto was the strong and coherent neighbourhoods. People didn’t live in the city so much as they lived in Cabbagetown, Chinatown, Little Italy and the like.

Read Also

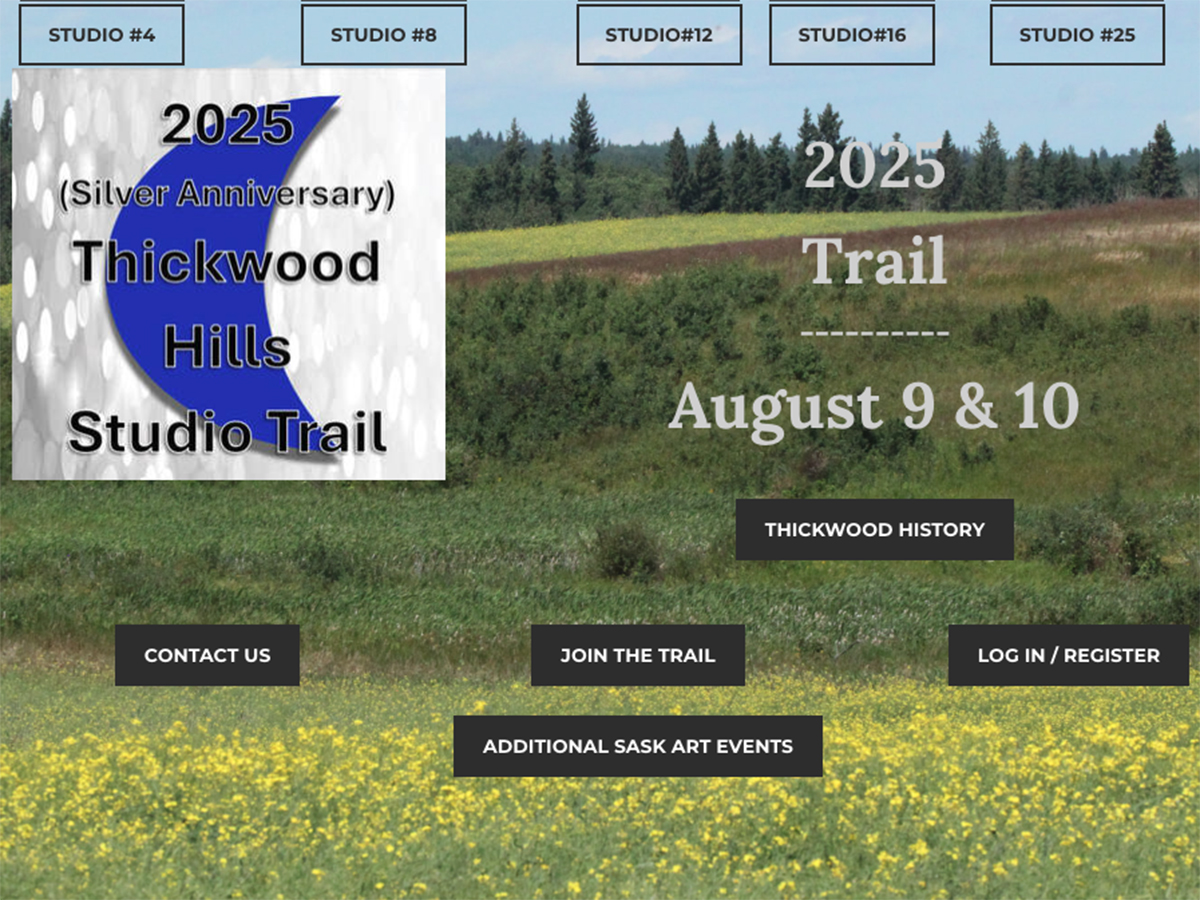

Art tour great reminder of talent hidden in the countryside

There’s a lot of talent hidden among the canola fields and cattle pastures of Western Canada that isn’t always noticeable from the highway or gravel road.

Toronto’s United Way Agency has now published a study that documents this growth in poverty and it focuses on Toronto’s once famous neighbourhoods.

Called Poverty by Postal Code, the study uses data from the census over 20 years to show how poverty has become more concentrated in more neighbourhoods.

In 1981 the number of families living below the poverty line in Canada was 13 percent. Toronto mirrored the country with 13.3 percent of families living in poverty. Since then, Canada’s poverty rate has declined slightly to 12.8 percent while Toronto’s has jumped to 19.4 percent.

When more than 26 percent of families in a neighbourhood live below the poverty line, the United Way study calls that a higher poverty neighbourhood. In 1981 the study identified 30 such neighbourhoods in Metropolitan Toronto.

In 1991, that number doubled to 66 and in 2001 it doubled again to 120. In 2001, 43.2 percent of Toronto’s poor families lived in these higher poverty neighbourhoods and 66 percent of all Toronto’s neighbourhoods now exceed the 1981 national average for families in poverty.

There are now more than 160,000 children growing up in these poor Toronto neighbourhoods. That’s almost the population of Regina (178,225) where the family poverty rate is only 11 percent.

If you think all this poverty is a function of unemployment, you’d be wrong. Ninety percent of all employable persons in these neighbourhoods have jobs, which is only three percent less than the rest of the city.

These people are hard-working people in minimum wage or part-time employment. They live in rental accommodation and a high percentage are new Canadians.

The single biggest factor contributing to this rising poverty rate is the high cost of housing.

This comes from the brutal elimination of government support for social housing and the failure of the market to provide a low cost alternative.

I moved into a mixed income housing co-operative in Toronto 25 years ago that provided 10 percent of its units as rent-geared-to-income. This is an example of the kind of program that was collateral damage in the war against the deficit.

The report calls this poverty by postal code. I call it poverty by policy.

The United Way argues that “no one should be disadvantaged or excluded from the mainstream, based on where they live.”

This is a point of view rural Canadians can understand.

Christopher Lind writes frequently in the area of ethics and economics. He is director of the Toronto School of Theology. The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Western Producer.