Otitis media, or middle ear infection, is a common bacterial infection in children that often requires antibiotic therapy.

Though this disease also strikes calves, it frequently goes undiagnosed because affected calves do not bellow in pain like afflicted babies. Many calves, more beef than dairy, have unseen infections.

Otitis media occurs in calves up to 18 months of age. In one dairy calf study, it was found in more than 20 percent of a herd’s calves over a two-year period.

Many were diagnosed too late in the course of their disease to be treated. The middle ear infection had already moved into the inner ear. In a few calves, it went further, triggering meningitis as it invaded the brain. Calves with this type of infection had to be euthanized.

Read Also

Worrisome drop in grain prices

Prices had been softening for most of the previous month, but heading into the Labour Day long weekend, the price drops were startling.

A calf can pick up an ear infection in several ways. The easiest way a bacterium can invade is when an infection in the outer ear breaks through the eardrum into the middle ear. Bacteria can also migrate to the middle ear through the bloodstream from an infection elsewhere in the body.

Bacteria can also travel from the mouth to the ear by entering the auditory canal, a tube that connects the oral cavity to the middle ear. This tube is an essential structure that stabilizes the pressure between the outer air and the middle ear. If you go up in an airplane, you know that yawning helps equalize pressure. It does this by causing your auditory tube to open.

This tube also provides an access for infectious agents to invade the middle ear once they have colonized the oral cavity.

The most common bacterium that causes bovine otitis media is Mycoplasma. Because this organism can also cause mastitis, calves probably pick it up when they nurse. It infects the oral cavity and then moves up the ear.

Ninety percent of calves have one-sided otitis media; only 10 percent have disease on both sides. More than half of all reported cases occur in calves between three and eight weeks of age when their immunity is still developing.

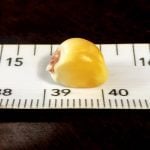

A calf with an ear infection is mentally dull, has a poor appetite and usually has a fever. Its ear canal may be filled with pus and emit a strong, unpleasant odour. Its head may tilt down on the affected side.

A middle ear infection can occasionally induce neurological signs. Nerves that supply the ear flap run alongside the middle ear, so the inflammation generated by the infection may damage the nerves, causing paralysis of the ear flap.

If a middle ear infection moves deeper, into the inner ear, it will affect the calf’s balance. It will have difficulty walking and appear unsteady on its feet. Its eyes may point to one side rather than forward and it may even have a nystagmus – a repeated side-to-side eye movement. This is likened to what your eyes do if you turn in circles and then suddenly stop.

If the infection penetrates even deeper, from the inner ear to the brain, the calf will convulse.

Otitis media commonly occurs in conjunction with other infections. More than half of calves with otitis media have pneumonia. This is not surprising because infections that start in the respiratory tract can move up to the ears. Affected calves can also have joint infections, diarrhea and umbilical infections.

Because otitis media is usually caused by a bacterial infection, it should be treated with antibiotics. Ideally, a veterinarian collects a sample of the ear debris and sends it to the lab for culture. Once the organism is grown, it is exposed to a number of antibiotics. The most effective one is then given to the calf. Without the benefit of culture results, most vets use tetracycline or another broad-spectrum antibiotic.

If the infection is deep in the middle ear and the eardrum is still intact, the calf can be given immediate relief by lancing the eardrum to promote pus drainage. This procedure often speeds its recovery.