HAPPY VALLEY-GOOSE BAY, Newfoundland — Just before the Trans-Labrador Highway reaches Lem and Darla Seaward’s farm, a road sign warns that the next services are 294 kilometres away.

It’s proof that the Seawards, who are the only egg producers in Newfoundland’s vast Labrador region, are literally perched on the brink of wilderness.

It has taken plenty of frontier attitude to face the daunting challenges of farming here.

The Seawards gained a lease to their land eight years ago. After clearing it, they slowly constructed a 45 x 12.5 metre barn, which holds a federally inspected grading station, egg storage, and the 5,000 hens their quota allows.

Read Also

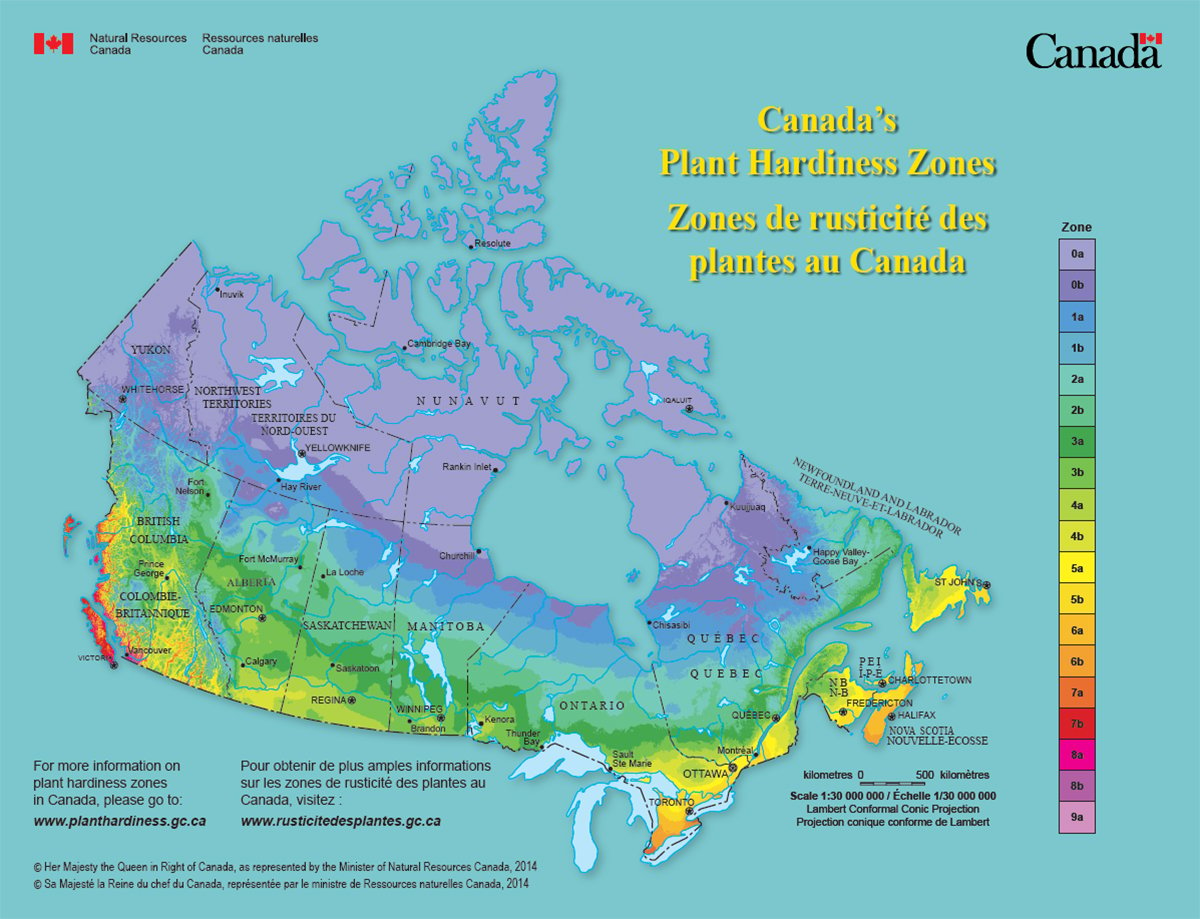

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Their birds began producing eggs four years ago, but they are still barely scraping by.

Last summer, the Seawards, who have four children, finally received government permission to move onto their farm. They moved a house trailer to the picturesque spot in November and quickly built an addition. It sits in a clearing surrounded by black spruce forest on the bank of the Churchill River.

Since they farm on crown land, they’re issued a lease for their 25 acres of land, with another 25 acres in reserve for future use. Someday they hope to get a land title — at least for the land where their house sits.

Darla said moving to the farm has helped them feel more settled.

“I think this year has been a good turning point in coming here.”

They’re still faced with daily challenges.

“Now we’re working on phone lines. We have no phone,” Darla said with a bubbly laugh that regularly breaks through the occasional edge of weariness in her voice. Right now they use a cell phone for all their calls.

Expanding their quota to make the farm more profitable is another challenge.

“The market’s here. We could double our size and not worry about where we’d send our eggs,” she said.

They sell eggs to the 9,000 people in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, which is the largest town in Labrador, plus a number of communities on the eastern coast.

“If we expanded, it would be west to Churchill Falls and Labrador City. We have a verbal agreement for them that they’d love our eggs.”

Last fall, they built a small horse barn, home to their pet quarterhorse and three other boarded horses. Next year, they plan to put in a grower barn. Instead of hauling in full-grown hens every year by truck, they could use a van to pick up day-old chicks in Quebec or Nova Scotia. Their feed also comes every eight weeks from Quebec.

Their long-term plan is to diversify.

“Our goal is to clear the land and raise beef,” said Lem, a native Labradorian who has been learning farming on the run.

Last summer, he experimented with a hay crop on their sandy soil, using chicken manure for fertilizer, and was pleasantly surprised with its success. He still needs to clear more land to make beef production viable, which means buying special equipment. His machinery wish list includes a baler, rake and tractor.

“Oh, it’s been a ride since we started,” he said with a laugh.

Darla, who grew up on a mixed farm in Illinois, said they’re both a bit crazy and adventurous to relish this undertaking. But they also have reminders of the beauty of frontier farming.

Sometimes in the midst of rushing about, she’ll suddenly spot the Labrador night sky with its brilliant stars and stunning northern lights.

“And I think, ‘that’s why we’re moving here.’ “