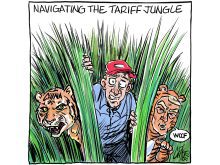

There is a ticking time bomb at the heart of the North American economy.

Canadian businesses and analysts have been pressuring the federal government to better prepare for the mandated renegotiation of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement that regulates trade and economic activity among the three countries.

Article 34.7 of the pact commits them to review the new agreement every six years, in 2026.

Read Also

Exports off to a slow start after last year’s torrid pace

Canadian grain, oilseed and pulse exports are off to a slow start, but there are some bright spots, according to the Canadian Grain Commission’s most recent weekly export data report.

This might not seem like a big deal. Canada has negotiated many trade agreements, and a regular review may seem reasonable. But USMCA is no regular trade agreement, in large part because this highly unusual review process undermines the very security and stability that trade agreements are supposed to provide.

In 2018, in the depths of the first Donald Trump presidency, Canada, the U.S. and Mexico renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement that had governed economic relations since 1994. The agreement was largely greeted with relief throughout Canada.

Negotiated under duress with an administration that threatened to tear up NAFTA, the three governments seemingly preserved a rules-based approach to managing economic relations with our most important trading partner. Free trade had been saved.

But there was a twist due to the requirement that the three countries review the pact every six years.

Trade agreements are bigger than their specific rules. Their real importance lies in how they provide the smaller partners with certainty and protection from the coercive power of the larger partners.

The promise of greater market access, and the threat of restricting this access, has always been the American trump card. American negotiators use this threat/promise to convince partners to adopt, change or eliminate policies in the U.S. interest.

But once an agreement is signed, the U.S. loses this leverage, which is good for smaller countries’ policy autonomy.

Having a trade agreement with a renegotiation clause is like having no agreement at all because everyone knows that, once renegotiations start, everything is back on the table. The renegotiation requirement significantly reduces smaller countries’ policy autonomy.

Knowing that renegotiation is on the horizon means the threat of economic blackmail will hang over all policies as they become pawns to be sacrificed to preserve the Holy Grail: access to the U.S. market.

Canada and Mexico run the risk of widespread regulatory chill: governments, anticipating retaliation, become excessively cautious in their regulatory efforts.

These chilling effects can already be seen, two years away from the start of formal renegotiations.

In a recent editorial, the Globe and Mail argued that Canada should make some enormous policy concessions — eliminate the new digital services tax, end the agriculture supply management system and crack down on forced labour in supply chains — in exchange for eliminating regular USMCA reviews.

Editorialists are labouring under the belief that free trade is still in play. It’s not.

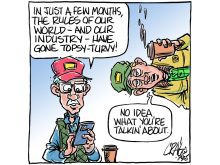

Ideologically, the U.S. is no longer the free-trade champion it was.

More pragmatically, any concessions are highly unlikely to convince the U.S. — regardless of which party is in power — to surrender the most potent weapon it has in its arsenal to pressure its neighbours to adopt its preferred policies. Policy reform, simply put, leads to U.S. market access.

While the U.S., Canada and Mexico will continue to sign trade and economic agreements, these deals are no longer reliable tools to deliver the certainty and protection enjoyed under NAFTA for three decades prior to 2018.

The 2018 USMCA didn’t preserve free trade in North America. It signalled its demise and the return of power politics to our most important economic relationship.

Blayne Haggart is an associate professor of political science at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont.