WINNIPEG — On any given day at a coffee shop somewhere in rural Saskatchewan, it’s a safe bet that the following topics will come up in conversation — the weather, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and what’s happening with farmland in the area.

Most of the time, the coffee talk around farmland is directed at two questions — who is buying the land and where are they getting the money?

Related story: Speculation about farmland ownership is running hot

The speculation around who is buying land can trigger a lively conversation.

Is Bill Gates buying Saskatchewan farmland? Maybe it’s David Thomson, the richest man in Canada. Is it a mega-farm from another part of the province?

The answer to the “who” is eventually answered when someone new moves into the area and they’re seen in the community.

The second question is more difficult to answer.

Who is financing the purchase of the land? Has a Chinese investor found a way, with the help of clever lawyers and co-operative locals, to invest $50 million in Saskatchewan farmland?

In most farmland transactions, it’s unlikely that foreign cash is flowing into Saskatchewan.

However, it could be happening because Saskatchewan is an agricultural behemoth.

It has 40 to 45 per cent of Canada’s agricultural land, and the provincial regulator that monitors farmland ownership has a tiny budget, similar to the price tag for one combine.

The Farm Land Security Board exists within the Board Governance and Operations Unit of Saskatchewan Agriculture. It has a mandate in the areas of farm foreclosures, home quarter protection and farm ownership.

In the fiscal year of 2022-23, the Farm Land Security Board had operating expenses of $830,372 for all of its activities.

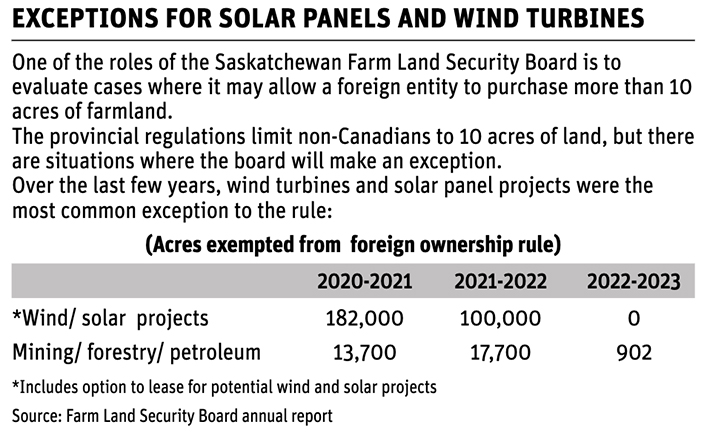

One of its primary roles is enforcing the province’s strict farm ownership rules. The regulations do allow non-Canadians to buy agricultural land, but the limit is 10 acres.

“Canadian citizens and permanent residents of Canada, and corporations or membership-based organizations which are 100 per cent Canadian-owned, and are not publicly traded, are eligible to own Saskatchewan farmland,” says a Farm Ownership page on the Saskatchewan government website.

A budget of $830,000 isn’t a lot, considering that Saskatchewan has 40 million acres of cropland and possibly 20 million acres of tame and natural pastures.

The value of all that farmland can be estimated using land prices from a Farm Credit Canada report released in March:

- Average value of cropland in Saskatchewan ($3,000 per acre) X 40 million = $120 billion

- Average value of pasture ($900 per acre) X 20 million = $18 billion

This means the Farm Land Security Board has $830,000 to monitor and enforce regulations for an asset valued at $138 billion. That money is also dedicated to its other functions, such as overseeing foreclosures.

An agriculture ministry spokesperson said regulating farmland transactions is a “significant undertaking” in Saskatchewan, but the budget is not an issue, for now.

“The board enforces ownership within the legislative framework presently in place, and the existing budget has not limited enforcement under the board’s current role, based on a primarily complaint-based system,” the spokesperson said in an email.

“If legislative changes were brought forward regarding enforcement, additional budget would be required.”

It’s unclear how many people work for the Farm Land Security Board. The 2022-23 annual report says salaries represent $480,000 of its budget and six people are members of its board of directors.

A real estate agent in Saskatoon who specializes in agricultural land, Ted Cawkwell, was surprised that the Farm Land Security Board had such a small budget.

However, the regulations and enforcement must be working because he’s the number one commercial realtor for Re/Max in Canada and sees almost no evidence of foreigners buying Saskatchewan land.

“I sell an awful lot of farmland. I have not, once, not one time, ever seen anybody who didn’t qualify … buy land,” said Cawkwell, who operates the Cawkwell Group.

“I don’t know if any (money) is seeping in or not. If it is, I don’t think there’s very much of it.”

The board doesn’t have the time or money to investigate every farmland transaction in Saskatchewan, but it does receive bi-weekly information on farmland sales and transactions from the Information Services Corp., which provides registry and other services to the provincial government.

A suspicious transaction in the sales data might trigger a red flag, but the board mostly responds to complaints.

“It (the board) investigates all complaints that come to its attention and can also conduct its own investigation or authorize a person to do so,” the spokesperson said.

“The minister of agriculture may direct the board to investigate an issue related to farm ownership.”

In the last couple of years, those investigations led to three fines and one case where the land purchaser was forced to sell.

“Since 2022, the board has ordered administrative penalties on four occasions,” the government spokesperson said.

“In three cases, the owner had land holdings of more than 10 acres; in the other case, a resident person had acquired land on behalf of a non-resident person.”

Besides investigations, the board may ask the owner or buyer of farmland to sign a declaration confirming they are Canadian citizens or permanent residents or that corporations buying land are 100 per cent Canadian owned.

However, such declarations are not mandatory for farmland transactions in the province.

They are required when the “board requests one,” the spokesperson said.

For instance, if the shareholder information is unclear, the board may ask for a declaration.

Some buyers may voluntarily sign a declaration, the spokesperson added.

The board also looks into the source of funds for the purchase of farmland to determine if non-Canadians are buying land in partnership with a local.

For more information on Saskatchewan’s Farm Land Security Board, its activities and its most recent annual report, click here.