A generational hydrological drought is occurring in rivers in southern Alberta, resulting in water levels rivaling the lowest seen in 50 years, the activation of a county’s emergency operations and a warning from the province.

“While it appears we will be able to complete the 2023 irrigation season without significant detriment, the situation could become more dire for the 2024 season if we do not receive a normal volume of spring snowmelt,” stated Alberta Agriculture Deputy Minister Jason Hale in an Aug. 28 letter to all the irrigation districts.

Hydrological drought refers to the effects of precipitation shortfalls on surface or subsurface water, such as stream flows, reservoirs, lake levels and groundwater.

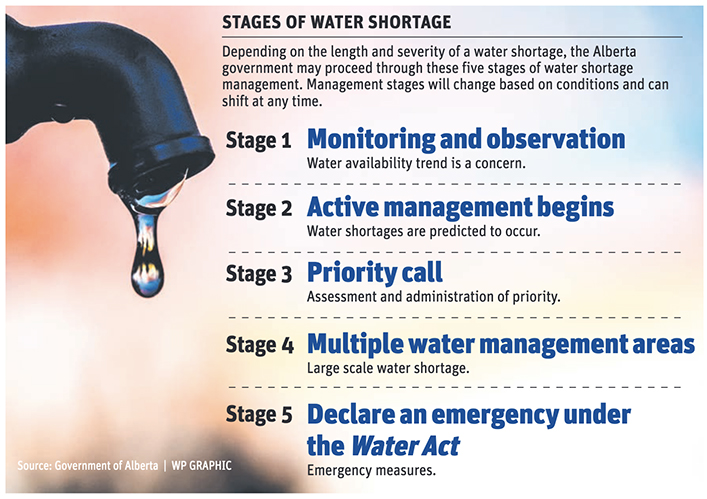

August also saw the province raise its threat assessment to Stage 4 of its Water Shortage Management alert system, one stage short of an emergency declaration.

The extreme conditions, which began in the spring with a below average snowpack that melted rapidly and wasn’t accompanied by the usual May and June rainfalls, have been exacerbated by a hot, dry summer and high demand.

With levels at the Oldman Dam falling to 43 percent of capacity by mid-August, the Municipal District of Pincher Creek activated its regional emergency management system because it could no longer draw water from the reservoir from its two intakes.

The situation is expected to continue for months, said the district’s utilities and infrastructure manager, David Desabrais.

“At least until we have a long-term solution in place or we’re likely talking into next spring — that’s the likely scenario right now, into next spring at minimum,” he said.

Desabrais said the district is looking at all options to maintain water supply into its water treatment plant.

“But some of the most promising solutions that we’re looking at are involving ground water wells that would tap into the Crowsnest River aquifer,” he said.

The district is currently trucking in water for its treatment plant and is providing services to other towns within the rural municipality except for the Town of Pincher Creek.

In 2001, the district faced similar circumstances.

“Projections show that the reservoir will be lower than it was in 2001, most likely, which puts us at risk for not recovering next spring as well. The situation is not ideal.”

Desabrais said the district’s four-stage water shortage management plan, currently sitting at Stage 3, will likely need to be updated.

Currently, moving into Stage 4 would see commercial business access to water restricted but would require something on the scale of a leak at the Oldman Dam reservoir to trigger.

The regional emergency operations team has been working well together, added Desabrais, after cutting its teeth during the 2017 Kenow forest fires, which swept through Waterton Park and environs.

“We’re using that resource to keep all the municipalities and stakeholders updated on what’s going on with our situation and make sure we’re working together if anything were to get worse,” he said.

Desabrais said it’s time for communities downstream to start preparations and those that don’t have restrictions in place should consider them.

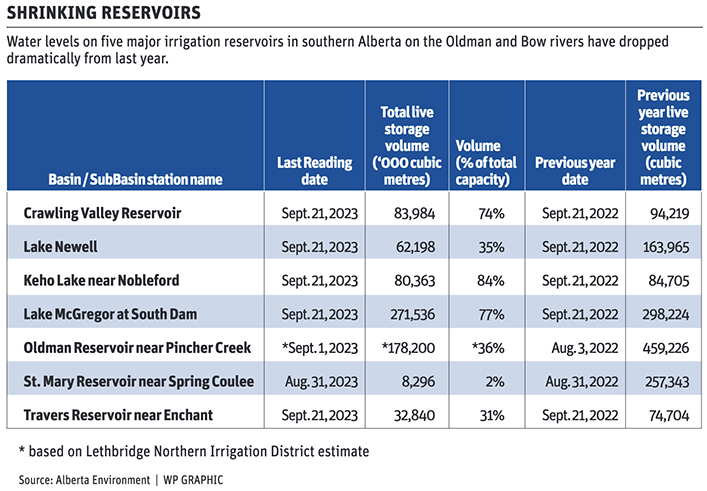

According to information in bulletins from the Lethbridge Northern Irrigation District, capacity at the Oldman reservoir was at 36 percent on Sept. 1, requiring more than 316 million cubic metres to fill, and outflows were reduced to 10 cubic metres per second into the main canal.

The cumulative daily stream flow running into the reservoir from the Upper Oldman, Castle and Crowsnest rivers is sitting at slightly more than seven cubic metres a second — 623,000 cubic metres per day — as of Sept. 24.

Water levels in the St. Mary Reservoir are at two percent of capacity. The St. Mary River Irrigation District shut down its system to irrigators Sept. 22.

While the Oldman River basin is stressed, the Bow River basin is faring better, although water levels at Eastern Irrigation District’s Lake Newell were at 35 percent of capacity as of Sept. 21. That’s more than 100 million cubic metres less than the same time in 2022 when the reservoir was holding more than 163 million cubic metres.

From an irrigation perspective, EID general manager Ivan Freisen is confident the district will make up the reservoir shortfall before the rivers freeze.

River flows have been weak throughout the year, which depleted reservoirs and led to the decision to shut down irrigation about 10 days early on Sept. 25, he said.

“That’s to provide additional time in the fall to bring levels to a more comfortable level for the winter,” said Freisen.

Current diversion rates from the Bow River support that comment with roughly more than 20 cubic metres a second being put back into the district, based on data from river reporting stations between Carseland and Bassano.

Freisen said those diversion rates will see the district get back to reasonable levels heading into winter.

Irrigators in the EID faced a possible July reduction in water allotment because of the weather and river conditions. The issue was rectified by rain in the mountains and through co-operative efforts of irrigators, said Freisen.

As for river levels downstream from where the Oldman and Bow converge to form the headwaters of the South Saskatchewan River, the strain is pushing the river management system to near its limits, but it is holding.

According to Cypress County’s Drought Management Plan, a minimum of 42.5 cubic metres a second from the South Saskatchewan River is required to meet Alberta’s interprovincial agreement to see 50 percent of the basin’s stream flows reach its eastern neighbour.

That level hasn’t been achieved at the Medicine Hat reporting station since Sept. 9, dropping to below 35 cubic metres a second at some points in the month, below both in-stream and water conservation objectives. But the shortfall has been made up from stream flows on the Red Deer River and the latest data from August show Saskatchewan is receiving 58 percent of the water from the basin.

In addition to communities upstream of the Oldman Dam reservoir, Calgary has mandatory residential water restrictions in place.

Lethbridge and Medicine Hat, as well as rural communities surrounding them, have voluntary restrictions in place.

Alberta Environment said it plans to hold meetings soon to address the situation with all the river user groups.

In southern Alberta, there are six water shortage advisories on the Oldman River basin, five each on the Bow and Red Deer river basins and one on the Milk River basin, while another 17 exist across the central and northern parts of the province.