Every year, new words become trendy or commonplace.

Few Canadians used the word “variant” at Tim Hortons back in 2019 — but it’s now spoken about two billion times per day.

For now, few farmers use the words “parametric insurance” in their daily conversations. That may soon change.

“There are new (parametric insurance) products coming out and it’s almost the sky’s the limit, in terms of what will be available. I think there will be a lot of products coming online that (will be) available to Canadian farmers,” said Andy Nadler, an agricultural meteorologist who runs Peak Hydromet Solutions on Vancouver Island.

Nadler spoke about parametric insurance during a presentation at the Manitoba Agronomists’ Conference, a virtual event held in mid-December.

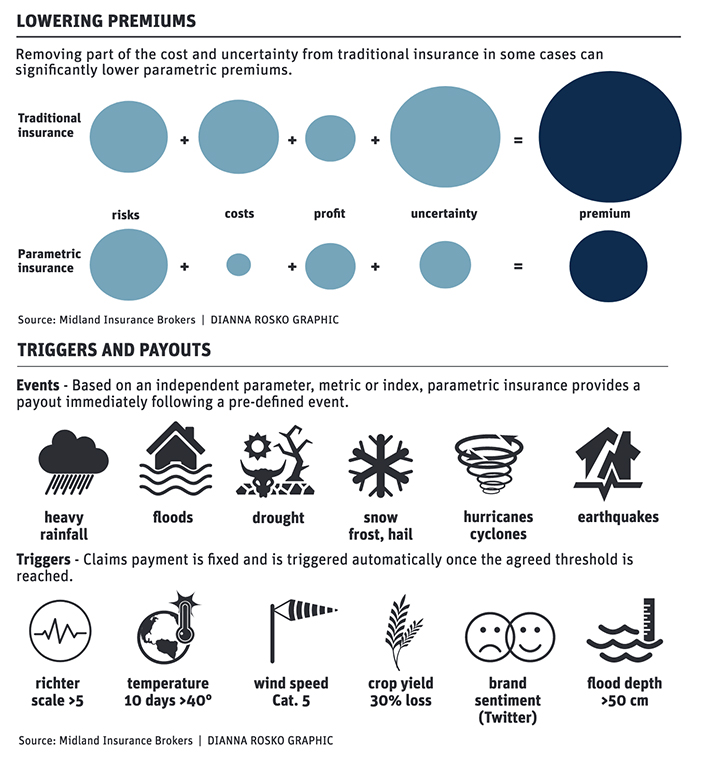

Parametric insurance, also known as index insurance, is coverage based on a metric. If the wind speed, rainfall or temperature exceeds a certain number, then a client receives a payment. It’s different than traditional insurance, where an adjustor looks at the damage and estimates the payment amount.

“Claim payment amount is fixed in advance… and triggered upon exceeding the threshold conditions,” said Marsh McLennan, a business consultancy, on its website.

Some parametric insurance is already available to Canadian farmers, such as canola heat-blast insurance, offered by Farmers Edge and other firms.

With canola heat-blast insurance, the metric could be critical heat degree days, heat blast units or some other measurement that tracks daytime and nighttime temperatures in June and July. Extreme temperatures above 30 C at bloom can reduce yield because it reduces the number of pods that form on canola plants.

If it is sufficiently hot during the canola bloom, the parametric insurance triggers a payment.

“If the threshold is met, the policy gets paid regardless of the actual damage that occurred,” said Nadler, who was an agriculture meteorologist with Manitoba Agriculture before moving to Vancouver Island.

“It’s extremely simple in that there is no adjustment or proof of loss.”

Another example is corn heat unit (CHU) insurance in Saskatchewan.

Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corp. provides insurance based on the CHU recorded at weather stations. If the CHU drops below 95 percent of normal, it triggers a payment.

“For every percent the accumulated heat units fall below 95 percent of normal… four percent of liability will be paid,” SCIC says.

It’s likely that global insurance firms will jump into Canada’s agriculture market, simply because they can. If a company doesn’t need an insurance adjustor in Saskatchewan or Alberta, they can provide coverage from Switzerland or South Dakota.

“One of the things with parametric insurance… there is less overhead, there is less necessity for on the ground resources like adjusters. Companies can offer it… from the other side of the world,” Nadler said.

One possibility could be soil moisture insurance, which would have been useful this summer.

If the soil moisture falls below a certain level in western Saskatchewan, as an example, farmers with soil moisture insurance would automatically receive a payment. If the shortfall of soil moisture becomes more severe, it would trigger a larger payment.

Parametric insurance may be simple, but it’s not perfect.

One risk for farmers is the data being used and how that data is collected. For rainfall insurance, will the data accurately reflect the amount of rain that fell on an individual farm?

In the world of insurance, this is known as basis risk.

On the Prairies, there is a network of Environment Canada weather stations, provincial ag-weather stations and private weather networks. But rainfall amounts can vary in a short distance of five to 10 kilometres as thunderstorms hit one field and miss another.

Some insurance firms also use satellite data to track soil moisture because that could be a more accurate measure of water shortages on a particular farm.

As for heat blast insurance, Environment Canada has excellent records on the frequency of 30 C to 35 C weather in late June and early July, when the canola crop is blooming.

But will that data reflect the likelihood of heat blast in the next decade, when the effects of climate change are taken into account?

“There’s good historical data… but what can we expect in the future?” Nadler said.

Plus, if years like 2021 become more common, where heat blast damaged millions of canola acres, the cost of such insurance will rise.

“As the risk increases, someone has to pay for it,” Nadler said.

Parametric insurance could become a normal way to manage crop production risk in Canada. It won’t replace traditional crop insurance, but could become a supplemental product, Nadler said.

“No doubt, there are going to be more options…. Once you start digging into the Insure Tech world, which is this more digital type insurance, it seems like there are companies popping up overnight.”