Drought adds to problem | Producers plagued by production and marketing challenges

(Reuters) — War and drought have crippled Syria’s wheat crop, with some experts forecasting output to fall to about a third of pre-war levels and possibly even below one million tonnes for the first time in 40 years.

Agricultural experts, traders and Syrian farmers gave crop estimates ranging from one million tonnes to 1.7 million at best, a more pessimistic range than that given by the United Nations earlier this month.

Before the war, Syria produced around 3.5 million tonnes of wheat on average, enough to satisfy local demand and usually permit substantial exports, thanks in part to irrigation from the Euphrates river that waters its vast eastern desert.

Read Also

Trade war may create Canadian economic opportunities

Canada’s current tariff woes could open chances for long-term economic growth and a stronger Canadian economy, consultant says — It’s happened before.

The last time its wheat harvest failed to exceed one million tonnes was 1973, although catastrophic droughts have pushed the crop close to that level in 1989 and 2008.

“One of the main factors limiting production is that it is becoming increasingly difficult to produce it given the extent of the war. There is genuine fear on the ground in traditional production areas and the risks are high,” said a Middle East-based commodities trade source with knowledge of Syrian grain markets.

The UN’s World Food Program had cited an estimate of 1.7 million to two million tonnes for this year and said that rainfall relied on for crops in Syria’s northwestern region was less than half of the average since September.

“There are a host of factors, starting from the start of plowing to soil fertilization to harvesting and transport and marketing, and the whole process is disrupted, all is reduced to a minimum level,” Hillal Mohammad, a UN agricultural expert based in Amman, said.

Before the war, the Syrian government typically bought around 2.5 million tonnes of wheat each year to distribute to bakeries that feed the public subsidized bread and to bolster its strategic reserve.

Government purchases of domestic wheat have declined and are expected to fall further as chaos caused by civil war and drought hurt the state’s ability to secure supplies.

Nearly a third of Syrians have either fled the country or are displaced within it, and parcels of territory are in the hands of rebels fighting to overthrow president Bashar al-Assad, where the government food distribution system has crumbled.

The agriculture ministry told state media earlier this month that wheat was being grown on three million acres of land but did not give an estimate of how much would be produced or bought by the government. Syria typically planted 4.2 million acres before the war, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Experts doubt the Damascus government’s ability to forecast figures accurately, citing the difficulty of gaining access to most crop growing areas.

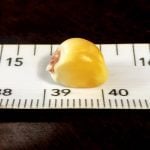

Yusef Abu Ahmed, a farmer in Atma, a northern village near the Turkish border, said by telephone that the length of wheat stalks was about 20 centimetres compared with 80 centimetres in normal years.

Some farmers have pumped underground water to compensate for poor rain, but the high cost of diesel has limited that choice for others in the western agricultural belt of Idlib, Aleppo and Homs, where wheat production is mostly rain-fed.

“Our wheat straw will end up being used for grazing because of the poor rain this season,” said Ibrahim al-Sheikh, a 36-year-old farmer in the plains of Halazoun, in rebel held northwestern Syria.

With drought hitting its rain-fed wheat crop in the west, the hope for Syria seems to lie in its irrigated crop lands in the east, which before the crisis constituted almost 60 to 70 percent of the country’s total wheat production.

Some local farmers told Reuters they have sown large tracts of land using elaborate irrigation canals and dams that preceded the crisis, and have escaped widespread damage.

The agriculture ministry says it set aside about 80 billion Syrian pounds ($540 million) to buy wheat and barley this season.

Still, even with the funds for procurement set aside and with irrigated lands escaping the drought, the government is not guaranteed to get its hands on the production.

“Even if there is production, marketing is severely disrupted,” the UN’s Mohammad said. “It’s getting worse for farmers getting seed and fertilizers, etc., and for the state’s elaborate procurement system, with collection and gathering centres almost no longer functioning,” he said.

In many parts of Syria’s main eastern breadbasket area known as al-Jazira, which spans Hasaka, Deir al-Zour and Raqqa provinces, the government is not in control. The area around the now rebel-held city of Raqqa alone produces around a quarter of the national harvest.

One local resident from a farming family said the militant Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISSL) that governs Raqqa and its rural hinterland have told farmers they are free to dispose of their wheat as they choose, even selling it to Turkish traders.

Government officials do have good access to areas in Hasaka, Hama and some areas in the northeastern part of the country near the Kurdish-held Qamishli city, another agricultural expert said on condition of anonymity. But the situation in the country overall remains murky.