As a farm reporter, at every event I attend for work — whether it’s a field day or conference — I’m continuously amazed at what I take away from it. Given the nature of the job, that learning is often ag-related, but just as often, it goes beyond.

For example, while attending the Indigenous Farm and Food Festival at Batoche, Sask., I learned about history and culture as well as agriculture and, most importantly, how those things can all come together.

It can be seen in the “three sisters” tradition: an intercrop of corn, beans and squash planted together for collective benefit to all three. The corn acts as physical support for the beans, beans fix nitrogen and squash conserves moisture as a ground cover.

Read Also

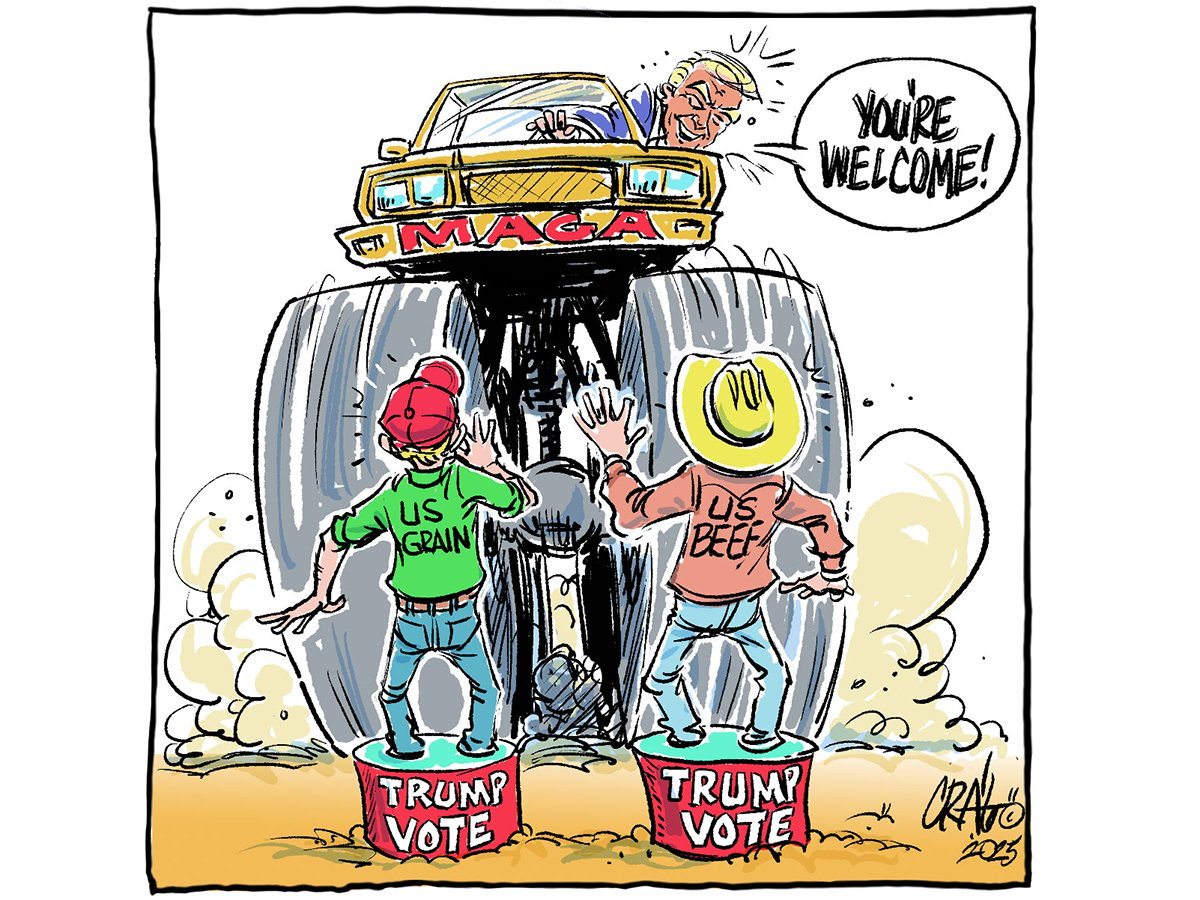

When the electorate votes against its best interests

U.S president Donald Trump has left many clues over the years that many of his actions weren’t going to necessarily be in the best interests of American farmers.

Indigenous people across North and Meso America have done this for generations, finding ways to adapt the tradition to their needs and climate.

The knowledge about intercropping was always there. It’s just that now we’ve got the science to explain why it works.

Why did it take centuries of post-European contact for the wider farm community to realize that “ancient” techniques, which had obviously passed the test of time for generations, actually proved to be beneficial for the plants, the land and human beings?

It’s a question that can be applied to gardening, cropping and raising livestock.

In a sense, it’s being addressed with the rising interest in regenerative or sustainable agriculture, movements with a notable number of practices that take their cue from traditional or natural systems and the science that is backing it.

One common theme at the festival, among farmers, organizations, agronomists and educators, was that the nature of modern agriculture and people’s mindsets toward it needs to shift; that over the last few decades, too much has been taken from the land and some effort needs to be made to give back if production is to continue.

At the same time, they did recognize that large-scale agriculture is a business and businesses need to make money.

It’s hard to entirely disagree, especially when the results of modern research and farmer experience reflects not only benefits to the land but also to their pocketbooks and productivity.

I feel that in a decade or so, many people will look at practices such as seeding marginal acres to forage, growing cover crops with commodity crops and livestock integration and ask why they didn’t do this sooner, just like other conservation practices, such as no-till and bale grazing, have found their way out of the margins and into mainstream farming.